For a few almost halcyon weeks towards the end of last year, hopes that the Government would act to tackle the social care crisis were building. No one would say it publicly, but there was a quiet optimism coursing through the sector that Whitehall would finally heed the growing calls.

Local government, which had been lobbying hard for months, was increasingly being backed by a diverse bunch of organisations, with the pièce de résistance viewed as NHS England chief executive Simon Stevens' intervention.

When the Autumn Statement set piece came and went with no mention of adult social care, hopes shifted to the local government finance settlement just before Christmas.

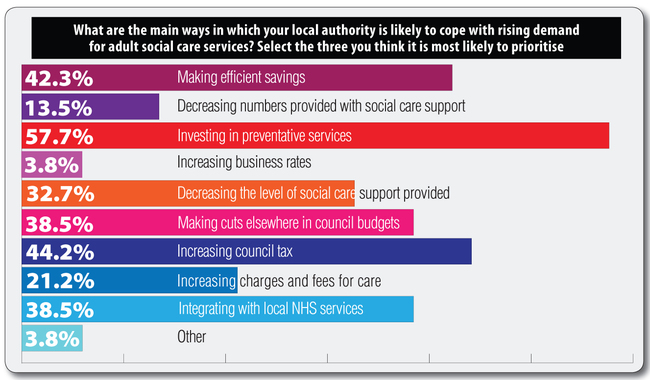

Whitehall's proposed solution disappointed many. By allowing councils to increase the adult social care precept by up to 3% next year and the year after, but failing to bring forward Better Care Fund (BCF) money, the Government missed an opportunity to do something substantial to help.

Since the finance settlement, The MJ and older people's charity Independent Age, have been taking the temperature of the local government sector by surveying key decision-makers, including adult social care directors, portfolio holders and council leaders.

The responses paint a depressing – if predictable – picture.

One London council leader explained: ‘How can I fully express the despair and anger felt by my councillors about the way central government is failing some of the most vulnerable people in our society by not properly funding social care and not allowing local government the devolved powers to step up to the challenge?

‘Central government needs to admit that the whole system is in crisis and neither the Department of Heath (DoH) nor the NHS have the means to resolve it. Only a full integration of health and social care and the full devolution of powers to health and wellbeing boards will allow local systems to invest in preventative services, help residents become more resilient and develop out-of-hospital care.

‘Place-based health, based in the community is the only way forward. DoH and the NHS need to get out of the way.'

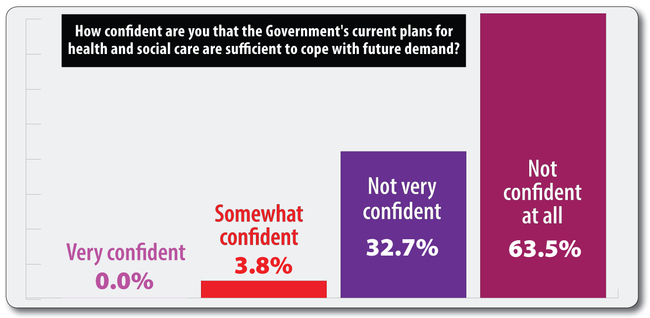

This level of despair was confirmed by our quantitative data, which found an astonishing 96% of respondents either not very or not at all confident that the Government's current plans for health and social care are sufficient to cope with future demand.

One north west cabinet member for social care explained: ‘We have attempted to organise three-year budgets based on the best information available in December 2016 but central government proposals regarding possible uses of business rates, New Homes Bonus, changes to public health ringfenced budgets, additional rises in the National Living Wage, etc, all undermine the financial basis upon which our council is attempting to bring forward sustainable adult social care provision.'

A south west council leader added: ‘The usual strategy of blaming local authorities for a problem is simply not plausible. The Government needs to start listening to local authority leaders for a change, rather than thinking it knows best about everything in the public services.'

Asked about our survey results, the Department for Communities and Local Government – perhaps significantly – passed the buck to the DoH, which insisted it ‘recognised the pressures of an ageing population'.

Councils are less convinced, with the leader of the Conservative group at the Local Government Association, David Hodge, hitting the headlines last week when he called a referendum on raising council tax by 15% at his authority, Surrey CC.

The relatively wealthy residents of Surrey, perhaps, have this option, but other local authorities are left gazing at the county's potential revenue from council tax with a misty-eyed sense of longing.

As one cabinet member for social care in the West Midlands wrote: ‘There is real concern in this socially and economically deprived borough that an increase in council tax may be necessary but it would add to the financial hardship already faced by so many residents.'

One north east director of adult social care added: ‘The social care precept will not solve the problem of inadequate funding for social care as it raises very little in the areas with a low council tax base and, in effect, asks the poorest people to pay more for social care. The amount it raises does not even cover the National Living Wage rise – never mind addressing the funding shortfall that providers of care have identified.'

A cabinet member in the North West piled in, writing: ‘In an authority like ours, with a very low council tax base, the precept that the Government allows brings in a small amount in comparison with the growing need in adult social care.

‘The extra money raised from the precept goes nowhere near to closing the gap caused by the year-on-year swingeing cuts to the revenue support grant.'

Ultimately, there needs to be more money in the system following years of significant cuts, though communities secretary Sajid Javid and prime minister Theresa May have both made clear the issues cannot solely be solved with more money.

Some have suggested full integration between health and social care, though 63% of our respondents were either not very confident or not confident at all that their local authority would achieve this by the Government's 2020 target.

One director said: ‘While integration is good for patients and service users there is little evidence of real cost savings to social care.'

A West Midlands council leader added: ‘The NHS is prioritising its own budget challenges in acute care before any innovative ways of working, ill health prevention or social care integration work.'

And a London director of adult social services warned: ‘As the funds to the NHS continue to remain at a standstill – at best – the creative opportunities that the Better Care Fund could offer are beginning to be diminished.'

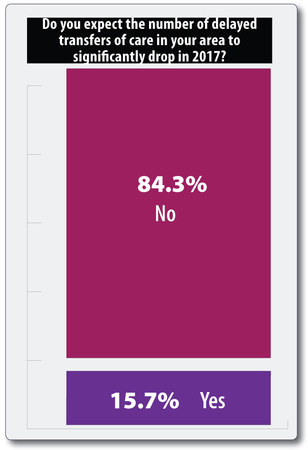

With pessimism over any improvement in delayed transfers of care pervading – 84% were not expecting a significant drop this year – the Government must come good on its promises.

If ministers fail, they may be haunted by the words of one of our survey respondents: ‘Current situation untenable. Future desperate.'

Analysis by Andrew Kaye, head of policy at Independent Age

The strong message emerging from this snapshot survey of key figures in adult social care is that there is a crisis in health and care. In fact, we can see staggeringly low levels of confidence that things will soon improve.

On delayed transfers of care, the results suggest local authorities feel they have very limited or no control over the problem. This is of concern, since delays owing to patients awaiting a care package in their own home is now the second biggest cause of delayed bed days overall.

It feels as though there is an impasse between government, the NHS and local authorities on delayed discharge and a sense of acceptance that these problems will get worse (or, at least, won't get better any time soon).

Overall, this survey tells us that local authorities have no confidence these issues will improve in the next year.

With the NHS and social care continuing to make headlines, all eyes are on the prime minister to now deliver on her promise that her government will bring forward a solution that will make social care more sustainable and improve delays from hospital.

We at Independent Age believe it is time to convene urgent cross-party talks and find a solution on health and care funding that improves the lives of millions of older people who rely on health and care services now and in the future.