The phrase ‘to paper over the cracks' means to use a temporary expedient, to create a mere semblance of order or agreement. The origin of this phrase is attributed to the Prussian statesman Otto von Bismarck. He used a corresponding German expression in a letter dated 14 August 1865 during the negotiations of the Convention of Gastein, a treaty between Austria and Prussia, which temporarily postponed the final struggle between them for hegemony over Germany: ‘We are working eagerly to preserve the peace and to cover the cracks in the building,' he is alleged to have said.

As of 2020, local authorities have faced a reduction to core funding from the Government of nearly £16bn, covering the preceding decade. That means councils have lost 60p out of every £1 the Government had provided to spend on local services in this time.

In the current financial year, 168 councils will receive no revenue support grant at all. This news has not been without impact as noted in the National Audit Office (NAO) report, Financial sustainability of local authorities 2018.

- Compared with the situation described in our 2014 report, the financial position of the sector has worsened markedly, particularly for authorities with social care responsibilities.

- Financial resilience varies between authorities, with some having substantially lower reserves levels than others.

- A Section 114 notice has been issued at one authority, which indicates that it is at risk of failing to balance its books in this financial year.

- While local government has coped admirably with this challenge, the report also notes the impact this financial impact has had on service sustainability:

- Local authorities have protected spending on service areas such as adult and children's social care where they have significant statutory responsibilities, but the amount they spend on areas that are more discretionary has fallen sharply.

- Local authorities now spend less on services, and their spending is more concentrated on social care.

- Local authorities have tried to protect frontline services in their savings plans. While this has been successful in some areas, there are signs that services have been reduced in others.

Analysis by the Local Government Association (LGA) contained in the report, Local government funding: Moving the conversation on, shows that local services face a further funding gap of £7.8bn by 2025. This represents the difference between the cost of funding services at the same standard as in 2017/18, against funding that the LGA estimated will be available to do so. This gap corresponds to keeping local authority services ‘standing still' and only having to meet additional demand and deal with inflation costs. It does not include any extra funding needed to improve services or to reverse any cuts made to date.

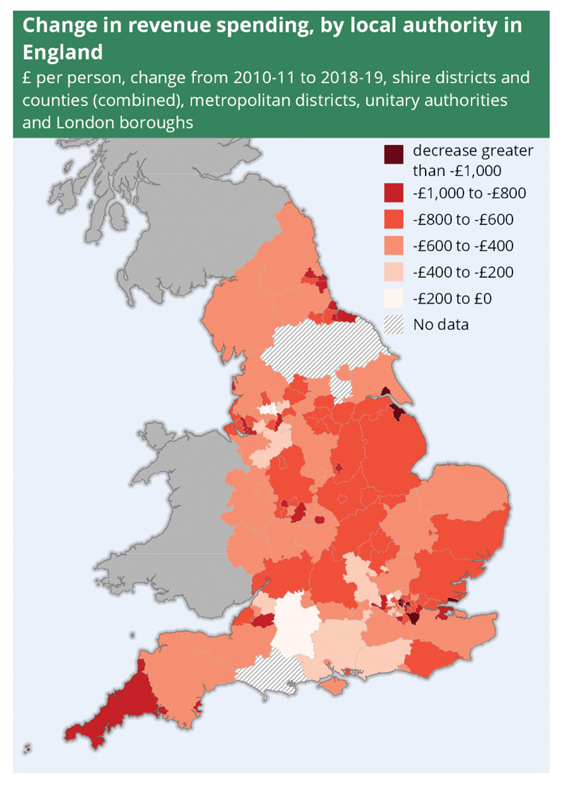

The national picture of this impact can be seen in Figure 2 – Change in revenue spending by local authority in England – covering the period from 2010/11 to 2018/19.

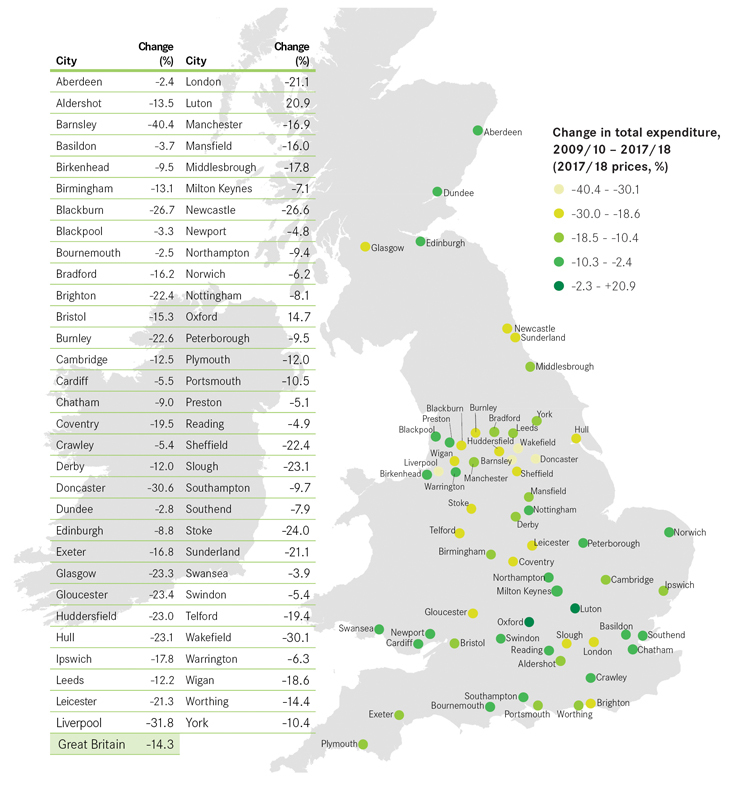

Centre for Cities in its report, A decade of austerity, sets out an analysis of ‘change in total expenditure' for the major cities in the UK, demonstrating that local government, particularly in urban areas, has been hardest hit by austerity. Reflecting the variation across Government departments, there has also been a great deal of variation within local government as to the severity of these cuts.

The Centre for Cities report concludes: ‘Looking at how these cuts to Government funding have translated through to spending on day-to-day services shows that cities have tended to see the deepest cuts. As a whole, there has been an 18% fall in the day-to-day spending by local government in cities between 2009/10 and 2017/18, compared to a 9% fall elsewhere.'

This analysis helps us to better understand the impact of the spending reductions in key cities within the overall regional analysis of the country.

Unsurprisingly, given the population density of the country where 83% of the UK residents live in urban populations, this spending reduction will have been felt most by those individuals and families living in these communities.

With funding to local government no longer adequately reflecting population changes or movements, it is easy to see why this is so critical to any future funding formula for the sector as a whole, but this is by far outweighed by the needs within our communities.

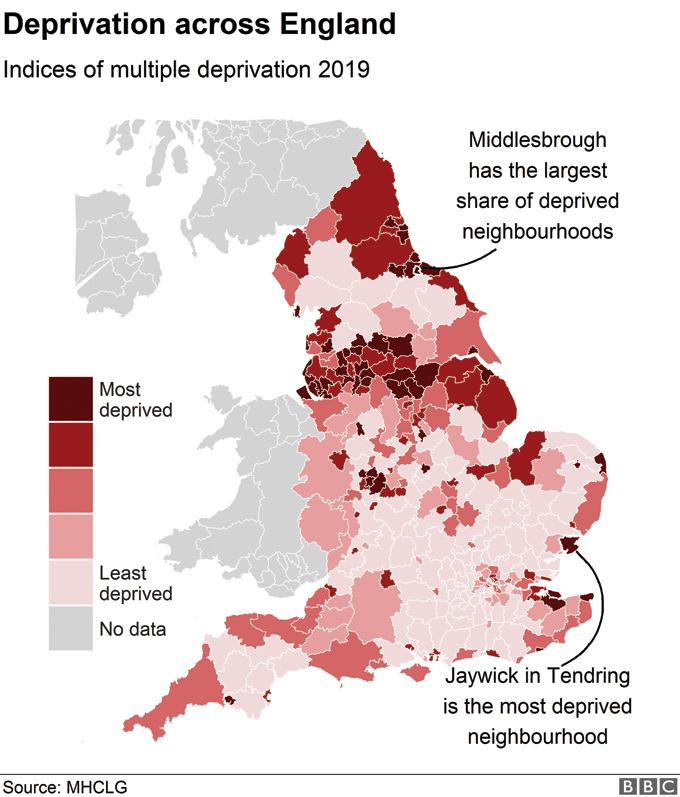

Figure 3, ‘Deprivation across England' (The Index of Multiple Deprivation – IMD 2019), demonstrates the national comparisons of deprivation. What is clear is that all places are not equal, all places have not been equally impacted by the challenges of austerity nor the choices that have had to be made by local politicians.

This brief analysis represents the starting line for the local government sector before the unprecedented challenge of COVID-19.

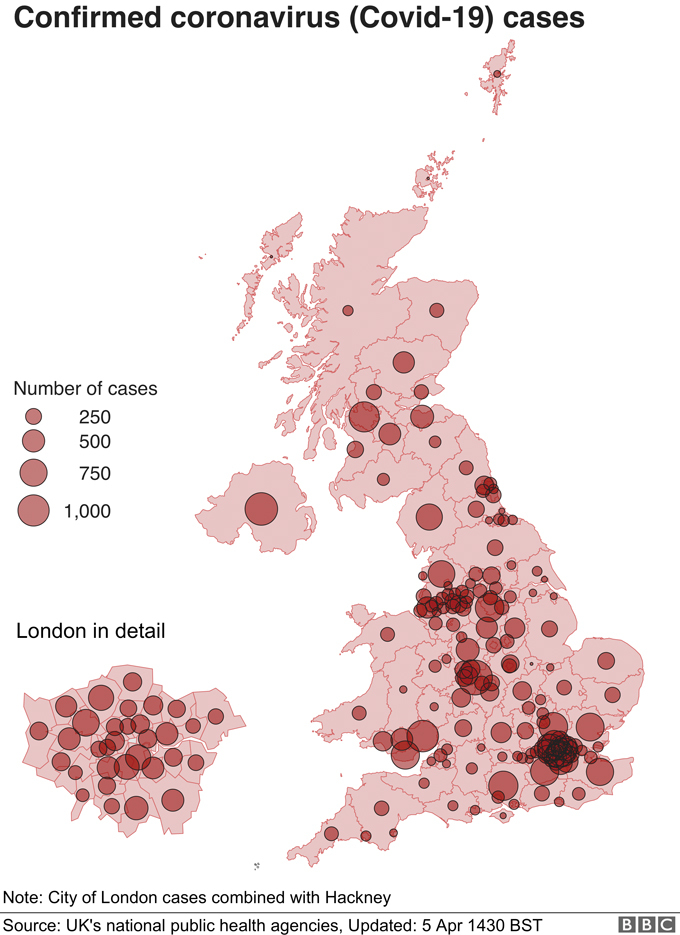

It is clear to see from Figure 4 ‘Confirmed coronavirus cases nationally' from April what the impact of austerity truly and sadly means.

The NAO's report of 2018 set out a sober warning, analysis and a reminder to the Ministry of Housing, Communities and Local Government (MHCLG) of its responsibilities and the critical area of focus. The Government sets statutory duties for local government to provide services, ranging from adult social care to waste collection.

The ministry has overall responsibility in central Government for local authorities' funding. This includes:

- Distributing the majority of funding voted by Parliament to support local authorities to deliver services;

- Taking the cross-Government lead in supporting HM Treasury on decisions about local government funding at major fiscal scale events; and

- Maintaining a system of local accountability that assures Parliament about how local authorities use their resources, including preventing and responding to financial and service failure.

Government policy dictates the overall levels and distribution of funding provided to the sector, and local authorities' statutory responsibilities.

While the department is responsible for the financial framework for local government and developing an overview of the overall service cost pressures faced by local government, responsibility for statutory services delivered by local authorities is spread across Government departments.

Each department is responsible for establishing its own arrangements to assure itself that services remain sustainable and that statutory responsibilities are being met.

These departments are also responsible for giving the department information on services to support decision-making at major fiscal events.

Since 2010, successive Governments have reduced funding for local government in England as part of their efforts to reduce the fiscal deficit.

Local authorities face a range of new demand and cost pressures while their statutory obligations have not been reduced. The scope for local discretion in service provision is also eroding even as local authorities strive to generate alternative income streams. The financial uncertainty created by delayed reform to the local government financial system risks longer-term value for money.

The department must also set out at the earliest opportunity a long-term financial plan for the sector that includes sufficient funding to address specific service pressures and secure the sector's future financial sustainability.

The department's capacity to secure the sector's financial sustainability in the context of limited resources is shaped by the priorities and agendas of other departments. The department's improvements in understanding and oversight are necessary but not enough.

Equally, because responsibility for services is dispersed across departments, each department has its own narrow view of performance within its own service responsibilities. There is no single central understanding of service delivery as a whole or of the interactions between service areas.

To date, the current spending review period has been characterised by one-off and short-term funding fixes. Where these fixes come with restrictions and conditions, this poses a risk of slowly centralising decision-making.

The current trajectory for local government is towards a narrow core offer increasingly centred on social care. This is the default outcome of sustained increases in demand for social care and of tightening resources. The implications for value for money to government from the resulting re-shaping of local government need to be considered alongside purely departmental interests. Departments need to build a consensus about the role and significance of local government as a whole in the context of the current funding climate, rather than engaging with authorities solely to deliver their individual service responsibilities.

Local government faces the unprecedented challenge of COVID-19 but it does balanced on a precarious cliff edge, such is the austerity erosion of any firm foundation.

The earliest instance in the UK of the phrase to paper over the cracks that can be found is from The Essex Standard, West Suffolk Gazette, and Eastern Counties' Advertiser (Colchester, Essex) of Saturday 16 March 1889, in an article on the question of whether Colchester should ‚at some time have a new Town Hall'.

Although the expense to the ratepayers will of course be felt, I fancy the erection of a new building might be worthily accomplished by the aid of generous subscriptions, and I think this cannot be much longer postponed by the old Colchester cleric's expedient of ‘papering over the cracks'.

Let us not paper over the cracks.

Nathan Elvery is former chief executive of West Sussex CC and Croydon LBC and managing director of Imagine Public Services