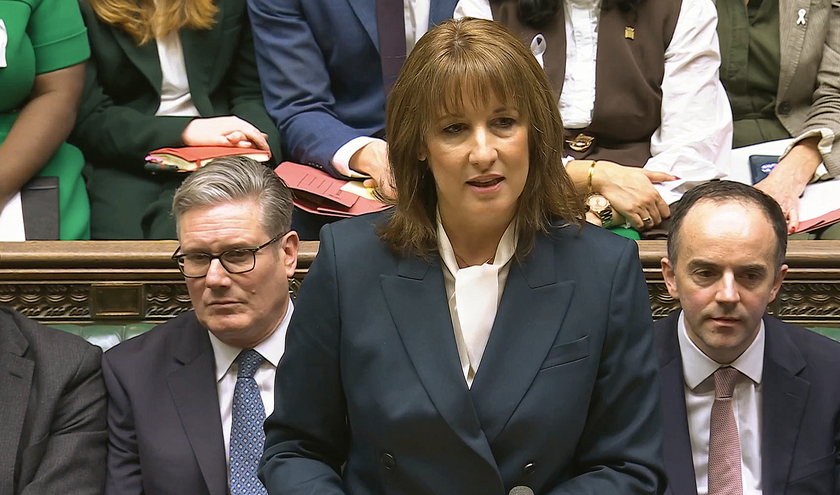

This week local government held its collective breath as Rachel Reeves stood up at the dispatch box to reveal her Budget. It would have been daft to expect too much – despite some excellent lobbying – as public finances are not in the greatest shape. Nevertheless, with so much to grapple with – local government reorganisation, the fair funding review, and the daily grind of coping with tight budgets and ever-increasing need – hope needed to be kept.

In truth Reeves was not dealt the greatest hand for a chancellor. For this Budget she had to somehow keep a plethora of interests happy, or at least not tip them over into open rebellion. The markets, the voters, the Parliamentary Labour Party, the North, the Red Wall, the metropolitan elites, the middle classes, the builders, the drivers, her Cabinet colleagues. How did she do?

There was an argument that the best tactic for Reeves would have been to go ‘big'. Push up taxes, even break manifesto commitments if she had to, so that she did not need to do it again this Parliament. Do it with one tool – income tax rates – so all is clear and transparent and done.

In one stroke, end the constant speculation about what way taxes may or may not go next time, a web of uncertainty that has been damaging politically and has had real effects on the economy. But going against manifesto commitments has its big downsides too, and highly visible increases in taxes for most people don't go down well, not least because the cost of living is still so high on people's agenda. An alternative, if taxes had to go up, was to do so with a host of ‘non-protected' taxes and not make any too big.

The trial of place-based budgets in five mayoral strategic authorities to test how the pooling of public service budgets in a place can break down siloes, unlock more funding for prevention and improve outcomes sounds like the welcome return of the much-missed Total Place.

In the end Reeves went for freezing tax thresholds, plus a wide range of other taxes, which has probably increased her fiscal headroom by enough (to £22bn) to allow her to cope with negative changes in the economy for a while.

Reeves also needed money to end the two-child limit – which should have some positive effects on the families councils look after – and to take steps to keep the cost of living under control – like reductions in energy costs, and freezing train fares and prescriptions.

On the other hand, the introduction of what she did not call a ‘mansion tax' makes sense for the economy and in fairness terms, but the money appears to be going the Treasury, not to councils, although the small print of the Red Book does say: ‘Revenue will be used to support funding for local government services'.

That may have been the focus, but there were some interesting things for lower tiers of government. The trial of place-based budgets in five mayoral strategic authorities to test how the pooling of public service budgets in a place can break down siloes, unlock more funding for prevention and improve outcomes sounds like the welcome return of the much-missed Total Place.

Tourism taxes, or a ‘visitor levy', is given the nod too, with mayors in England having the freedom to invest in local economic priorities with this new power and the Government saying it will ‘explore the option for this power to be extended to the leaders of other strategic authorities'.

Could this be the beginning of a slow move to some sort of fiscal devolution?

Local government appeared in the Office for Budget Responsibility (OBR) papers but not for a great reason. In predicting increased pressure on spending over the forecast period, the OBR pointed to local authority borrowing being much higher than they had previously thought before and that a lot of this was due to ‘substantial recent upward revisions to outturn and rapidly growing spending on special educational needs and disabilities'.

The Government said that ‘future funding implications will be managed within the overall government DEL [Departmental Expenditure Limits] envelope' so they ‘would not expect local authorities to need to fund future special educational needs costs from general funds, once the Statutory Override ends at the end of 2027-28'. This is a very important move – although it is, as yet, unclear how this will be met within the existing Department for Education budget.

The detail in this Budget needs to be analysed and digested. The political battle to frame its message is already at full throttle with the opposition parties trying to badge it as tax rises to pay for welfare. But if this set of measures can now lead to some stability that both the business sector and the public crave and that allows growth to emerge then we will all gain.

Dan Corry is chief economist at the Future Governance Forum and a former Treasury and Downing Street economic adviser