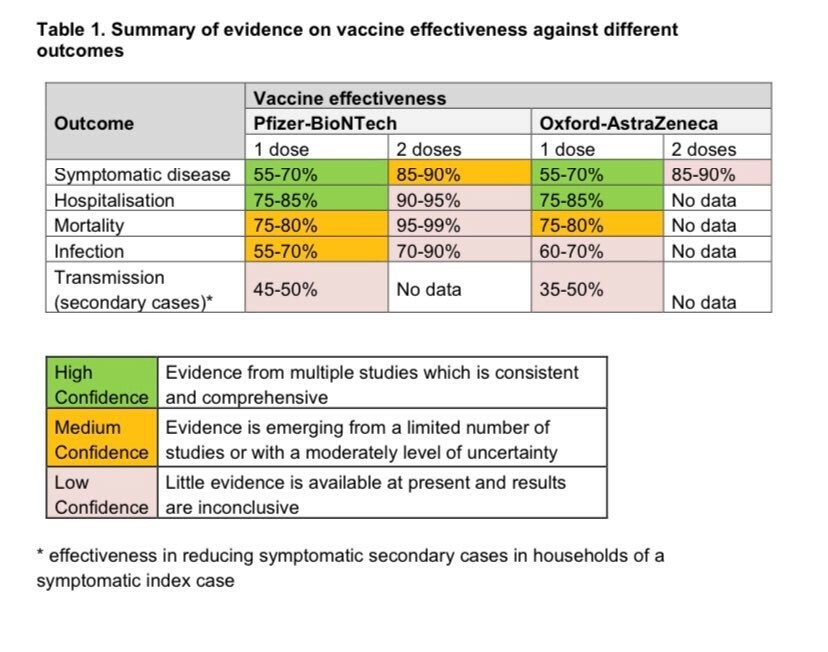

Last week Public Health England published its latest vaccine surveillance report. They estimate that 13,000 deaths have been prevented in people aged 60 or over in England and that 39,100 hospital admissions in people aged 65 or over avoided. At the same time two doses of either the Pfizer or Oxford/AstraZeneca vaccine provide between 85% and 90% protection from symptomatic disease. And the vaccine seems to reduce both infection in those who have received it, and is estimated to reduce transmission to others by a third to half.

Add to this the fact that 60.6m people have had one dose of the vaccine and 22.2m have been fully vaccinated and what's not to like? There is debate about how effective the vaccines available are against the Indian variants but early data from PHE does not suggest they are significantly hampered in their effectiveness against variants. Yet.

No vaccine is ever 100% perfect, but so far the available vaccines have done some real heavy lifting for us. So much so that we risk forgetting that they are not a magic bullet.

Most major disease outbreaks have been brought under control not by one single intervention, but by a cumulation of multiple small ones. For HIV it was safer sex, clean needles, treatment to reduce peoples' viral load to undetectable and pre-exposure prophylaxis (or PrEP) and more. For COVID it will be the same: testing, isolating infected people, preventive measures to stop airborne spread indoors, social distancing and vaccination. And more. Getting that message across remains a key to exiting the pandemic. The fewer infections, the fewer variants, and the better chance the vaccine has. The Association of Directors of Public Health guidance Living with COVID articulated this in more detail.

But it is arguable that the first tranche of the UK strategy – reduce deaths – has worked, and worked enormously well. There remains work to be done, because several challenges remain for us. And UK vaccination strategy needs to consider these. But we need to recognise that the current strategy has had a significant impact.

At the time of writing, trials are recruiting for vaccinating children, policy consideration on whether children need to be vaccinated for reasons public health or clinical are yet to be concluded. Booster studies are underway. I choose to see these as welcome signs that our evolving vaccine strategy will be informed by science.

For the next stages, there remain four pervasive ‘wicked problems' we still need to address, and the capabilities of local government will prove themselves central to addressing these.

- Inequity in vaccination

- Eradication or elimination

- Variants

- Enduring Transmission

There remain significant inequities in vaccination access and uptake. In February I wrote in The MJ that removing structural barriers to getting the vaccine, improving confidence among professionals and people to be vaccinated, getting really good granular data and addressing disinformation by trusted, accurate and easy to understand information were the Big Four to fix. That remains the case. The efforts of local public health teams on these has made an enormous contribution. But more remains to be done. And these efforts will remain crucial whatever strategy is chosen on the other three challenges.

It is no easy task to decide what should come next on the remaining three. It's easy to criticise the UK vaccine strategy for not having a clearly articulated ‘end game' for COVID. That would be unfair. The aim of reducing deaths using the vaccine was and remains sensible. If you don't know it reduces transmission, you can't very well build your strategy around that as a cast-iron commitment. As the data on what the vaccine does is emergent, so the strategy is able to evolve.

The most challenging problem we face is identifying and getting to the overarching end game for COVID - eradication or elimination. Do we want eradication - to get to very low COVID in a local area or elimination - a permanent reduction to zero? I don't believe we can get the latter without the former- low COVID before no COVID. Eradication may be possible, and the vaccine has a role in this but at a currently mooted 50% reduction of transmission the vaccine will still need other preventive measures alongside it. Equitable coverage will be key. We've all heard it – no one is safe until we are all safe –it's true. High levels of equity of uptake in the UK and globally are equally vital for eradication. But the need for other measures besides vaccination (such as testing, trace and isolate to pick but one) remain.

That brings up the issues of variants and enduring transmission. On both of these areas there seems at present much more opinion than there is hard evidence. Variants emerge frequently from coronaviruses. Sooner or later one may well evade the ability of the vaccine to protect against it. This has led a number of people to suggest early prioritised vaccination to populations at highest risk of new variant spread should be considered.

‘Enduring transmission' is a new term for what seems to be ongoing multiple outbreaks and transmission of COVID which keeps transmission at an endemically higher level than we would want. Multiple factors like houses of multiple occupation, inability to afford to self-isolate, multi-generational households , poverty and occupations where exposure is higher and transmission more easy are all implicated here. There are arguments on multiple sides that the use of early and prioritised vaccination for these areas should have been used to prevent this.

Both enduring transmission and high levels of variant transmission are associated with areas of deprivation. We risk a situation where some parts of our population – those least able to withstand the burden of COVID – are more exposed to enduring transmission and more exposed to variants.

There is, in my view, as yet no single or even clear answer yet. It has been pointed out that multiple changes to the vaccine strategy bringing in additional targeting would have slowed down roll out to everyone. At the same time, if the vaccine achieves some but no greater than 50% reduction in onward transmission (still unclear) then even if it plays an enhanced part over other areas, the vaccine by itself does not replace the need for a multifactorial strategy to address variants and enduring transmission. That may come as small consolation but there are no perfect solutions open to us.

There is a way out of this. And like anything with COVID, it isn't simple. During this pandemic we have drawn out evidence and learning at a pace which would have astonished us even six years ago. The key to this remains multiple interventions, alongside vaccination. And underpinning this a spirit of collaboration and listening to each other. Dogmatism on any side of this debate right now helps nobody. And waiting for a perfect answer before acting can kill.

No vaccine is ever 100% perfect, nor is any strategy we have at present. But the UK strategy of making several vaccines available and vaccinating people largely based on risk of mortality seems to have been well judged in hindsight. Only by working together will we find the optimal role for vaccination in the next phase of our endgame for COVID.

Jim McManus is director of public health at Hertfordshire CC, vice president of the Association of Directors of Public Health and a member of the National Vaccine Equalities Steering Board

@jimmcmanusph