The advantages of a thriving civil society are often cited and the challenges facing the sector well documented. What's often less clear is how we practically go about strengthening civil society to support the more resilient communities from which we all benefit. With the apparent political will to reconsider how we govern, both nationally and locally, the 2020s offer us the opportunity to truly realise the potential of places.

This reimagining of how we govern places is something I have been pushing for since taking office. It is the reason why, for the past four years, we have been taking steps towards a new model of city leadership, one which includes civil society more fully.

Part of our city's journey has involved re-understanding what we mean by civil society and being clear about what it is not. It cannot simply be viewed as what is left over when the formal organisations, in particular public services, withdraw. The danger in taking this view is that you prioritise public services over an asset-based approach to communities.

Civil society includes those organisations that step forward with services to fill the gaps left by public services, but it is much more than that. We must recognise civil society as a good in itself. It can be considered both evidence of, and a source of, power and resilience in our communities, not merely responding to context but shaping that context.

In Bristol, we've put civil society at the heart of our approach to city leadership. I describe it as moving beyond local government, and the disproportionate focus on the formal political and public managerial structures, to city governance. City governance recognises that the city is led and shaped by a web of formal and informal decisions and non-decisions of many place-shaping actors, including unions, business and civil society. It treats power as a collective act rather than zero sum.

The challenge we have is to grow the structures and cultures that enable us to bring order to the complexity of the city's leadership landscape. We call this our ‘One City Approach', in which civil society leaders are at the table as equal partners determining the city's priorities. That is where I believe civil society is in its fullness. It's found not merely in achieving a well-funded status or acting as a counterweight to the power of government or business, but as a true partner in governance, shaping the priorities and actions of other partners and helping to create the conditions in which civil society organisations can flourish.

The collective power we can leverage in places is considerable. In July 2016, I organised the first of what we today call our ‘City Gatherings'. 70 to 75 leaders attended from local government and the public sector, education, business, unions and civil society. A quick calculation suggested that between us we employed over 70,000 people and had a financial footprint in the city of over £6 billion. I talked to the room about our interdependences. Our businesses need a resilient workforce. This requires good population health, which relies on strong health services, but is also partly determined by quality work, housing and strong connected communities. I asked the room ‘With all the influence represented here today, if we, this morning, decided to agree and focus our collective firepower on just three priorities for the city, what could we not do?'

And that is what we did. These meetings now happen every six months and are the backbone of our collaboration in the city. We intend for them to have the culture of a ‘village hall' meeting, where the city comes together to agree what we want to get done. Our collective focus is captured in our ‘Bristol One City Plan', which holds our agreed vision of what we want Bristol to be like in 2050 and the sequence of opportunities, challenges and outcomes we need to meet year-on-year to get there.

We recognised that an empowered civil society strengthens communities and stronger communities are more resilient in the face of shocks, as we have experienced with COVID. This resilience is, in part, found in the networks of relationships that meet immediate needs.

In Bristol, we are fortunate to have had in place the network of relationships needed to face challenges long before COVID. An example of this is the collective effort to reduce food poverty in our city, in which community organisations, faith groups, businesses, as well as political and public sector leaders, jointly made a commitment, and contributed the resources necessary, to tackle hunger for our citizens. Our ‘One City Plan' makes 2026 the year by which we:

‘[R]educe the need for foodbanks in Bristol by tackling the root causes of food insecurity (the ability to secure enough food of sufficient quality and quantity to allow you to stay healthy and participate in society).'

In response we have run holiday hunger and food literacy programmes, while simultaneously taking on the food system with the aim of increasing the availability of locally grown food. I have made a political commitment, and business and schools are supporting the efforts, but the work is largely being led by the network of community organisations such as food banks and faith groups. They have not only distributed food but have been driving forward the work around how food is grown, distributed, consumed and disposed of, recognising that each of these factors contribute to the conditions that make food insecurity more likely.

By the time lockdown hit, the structures that had been put in place in the previous years reoriented themselves to the urgency of the moment, getting food to isolated families while also helping shape the overarching COVID response. That is a city benefitting from the time taken to invest in relationships and make space for the leadership and priorities of civil society organisations.

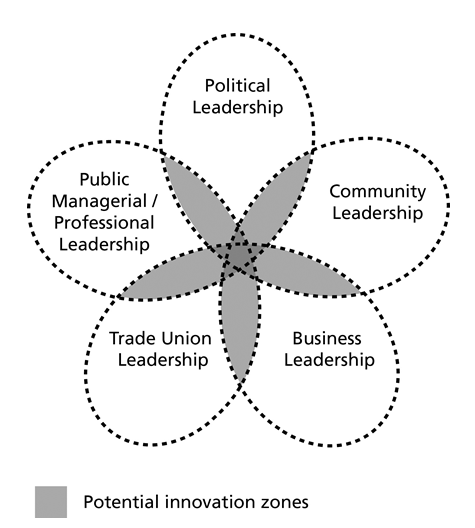

Professor Robin Hambleton's model of the realism of place-based leadership and innovation zones in the modern city captures this relationship and has provided the intellectual underpinning of our approach.

The point Professor Hambleton makes is that this is not a Venn diagram where any circle can be pulled away without impacting the properties of the other circles. This diagram is made of one continuous line and weakening one will distort the others.

I have also taken insight from Stephen Covey's The 7 Habits of Highly Effective People. In his book, the first three habits surround moving from dependence to independence and the next three habits focus on interdependence. Covey asserts that dependent people rely on others to get what they want. Independent people are able to get what they want through their own effort. This is where we found the ambitions for civil society to have plateaued, in its movement from dependency on governments with all the power, to a state of independence where it can hold government accountable.

And yet the highest status according to Covey is actually interdependence, where people (and for the purposes of this essay I would say organisations and sectors) combine their own efforts with the efforts of others to achieve their greatest collective success. In Professor Hambleton's model this gives rise to what he calls ‘Potential Innovation Zones', where the most relevant, dynamic and successful leadership takes place.

Of course, no single sector or actor can make this kind of shared leadership a reality. It takes a cultural shift and has led in Bristol's context to our ‘One City Approach'. It's what we sought in that first city gathering and what we have aimed for in the engagement with our city's voluntary and community sector in city leadership. For Bristol, strong doesn't exist in isolation.

This is not to be taken as a case for small government. It's a perverse exploitation of the benefits of a strong civil society to use them to justify the withdrawal of government investment.

But while this is not a case for small government, it is a case for government that distributes power – a sign of strong and confident government. The vehicle for this today is devolution. By devolving finance and powers to local government, central government puts that finance and power closer to civil society. If that local government is then minded to make the move from government to governance, you have the conditions in which civil society organisers can take up equal standing alongside governance partners and lead the places in which they live.

There are challenges to this. In the UK certainly it is not in the DNA of national politicians or civil servants to devolve power. The language of political leadership, and the journalistic commentary it dances with, betrays the underlying belief that the solutions to our challenges are to be found in rooms in Whitehall and Westminster. The more complex and impossible the problem, the tighter national political leaders control information and grip decision making. I understand their fear - they don't want to depend on, and be accountable for, decisions made elsewhere. The irony is that this fear constricts innovation and creativity and the likelihood of success. We have seen this played out throughout Brexit and in the response to COVID.

Contrast this with our approach in Bristol where, in December 2019, Avon Wildlife Trust introduced an item at our City Office Environment Board on the need to protect nature. We invited them to consider what our city response should be and in February 2020, with the support of city governance partners, they brought to political cabinet a paper declaring an ecological emergency. The outcome is that Avon Wildlife Trust proceeded to lead partners from the public sector, unions, business and politics in writing Bristol's ecological strategy. The strategy was published in September 2020. It's an emergency that wouldn't have been recognised and prioritised, and a strategy that wouldn't have been written, without making space for civil society leadership. That innovation and success would have been lost to us.

Government has been increasingly using the language of devolution and grassroots empowerment. But we need to be very careful of illusory devolution. It comes like this: London-based civil servants channel money direct to grassroots civil society organisations around the country. For all intents and purposes, this looks like community empowerment, but it is not. First, it's a funding relationship not a governance partnership. The funded organisation must meet a criteria and performance framework that was not created in the place they work or with their influence. That is disempowering. Second, the money bypasses local governance and by establishing the line of accountability with London, rather than the place in which the work is done, it strengthens the distant powers of London rather than locally accessible powers of the place. The kind of devolution we need must focus on building the power of local place-based governance.

There is a final opportunity that extends from this. I have consistently argued that we urgently need international governance to move into its next iteration, one in which the leaders of cities are equal partners in shaping national and international policy.

My argument is not merely to give local and city political leaders the space to contest the power of national leaders. City power is closer to civil society. If cities have the platform to shape national and international policy, it brings that national and international policy closer to civil society. A global network of cities shaping policy on topics as varied as climate, migration, pandemic preparedness and urban security would offer a framework through which civil society can network and influence internationally. To me, that is possibly the most exciting opportunity, not least because I have come to the conclusion that what we face today is not merely a crisis of ideas but a crisis of governance, a turgid model built in the post war years that lacks the openness to change and the ability to take on today's challenges.

There is a very real threat of potential disengagement amongst many of our civil society leaders if we fail to work more effectively together. These are organisations that represent often vulnerable or marginalised people that public sector bodies cannot or will not. If we are serious about building more sustainable and resilient places, engaging with civil society offers unparalleled opportunity.

In Bristol, we are already reaping the benefits and have trialled an approach that I hope other places can learn from. In spite of the challenges presented by the first year of this new decade, I look forward to what will be achieved in collaboration with civil society in the 2020s.

Marvin Rees is the Mayor of Bristol

[1] R Hambleton, "The New Civic Leadership: Place and the co-creation of public innovation", Public Money & Management, 39(4), April 2019 ,271-279