This Autumn Budget was a tax-and-spend event, with the chancellor introducing significant rises in wealth and property taxation as part of a broader effort to restore fiscal stability and fairness. Yet for all the emphasis on responsibility and redistribution, there was little reassurance for overstretched public services. For local government, the Budget left key questions on fiscal devolution, local revenue-raising powers and the future of council tax unresolved.

While ministers framed the Budget as a stabilising moment, the measures announced provide limited clarity for councils attempting to plan sustainably. New levies are being introduced, long-standing financial pressures remain and major policy details have been deferred to the forthcoming funding settlement or "the New Year," leaving real operational and financial risk in the immediate term.

The most prominent local tax measure was the so-called ‘mansion tax' -- real name, the High Value Council Tax Surcharge (HVCTS) -- a charge on properties valued above £2 million from 2028/29. MHCLG confirmed it will sit on top of existing council tax bands, with valuations undertaken by the VOA and collection by local authorities.

The levy has potential. Properly designed, it could strengthen local investment in visitor economies, support services in high-demand areas and align England with international practice. Yet two limitations were evident. First, it will apply only to mayoral areas, tying fiscal powers to governance structures rather than local economic need. Second, MHCLG provided no clarity on revenue retention, leaving open whether councils will genuinely benefit.

Yet the crucial detail is that revenue will accrue to central government, not directly to local budgets. While ministers say proceeds will "support funding for local government services," the mechanism effectively guarantees equalisation within the national settlement. Councils in areas generating the surcharge are unlikely to see a net benefit.

This creates two concerns. First, it blurs the link between local taxation and local decision-making, risking confusion among taxpayers who may assume contributions fund local priorities. Second, it adds complexity to an already outdated council tax system without addressing structural inequities. A national surcharge is not meaningful reform.

The government also confirmed progress on a visitor levy, intended to support mayoral combined authorities. The consultation is underway, but implementation is unlikely until 2028/29 after legislation and system changes are completed.

The levy has potential. Properly designed, it could strengthen local investment in visitor economies, support services in high-demand areas and align England with international practice. Yet two limitations were evident. First, it will apply only to mayoral areas, tying fiscal powers to governance structures rather than local economic need. Second, MHCLG provided no clarity on revenue retention, leaving open whether councils will genuinely benefit.

Both HVCTS and the visitor levy highlight a recurring tension in local finance: councils are accountable for delivery but constrained in the tools they can use to fund it. New revenue streams are framed as local measures, but in practice are centrally mediated.

The Budget also confirmed a 0.5% reduction in departmental spending limits, which MHCLG indicated would likely translate to around a 0.1% impact on local government once council tax and retained business rates are factored in. While this provides short-term reassurance, it does not remove the broader challenge: councils are expected to manage national fiscal tightening alongside a funding system increasingly misaligned with local demand.

The SEND financing situation illustrates the same dynamic. The Budget confirmed central funding for SEND from 2028/29, a welcome long-term shift. Yet no clarity was provided on how historic deficits should be addressed or how councils should manage the next two years as demand continues to rise. Councils remain accountable for delivery but without the certainty required to plan budgets, hire staff, or invest in early interventions – a challenge mirrored across other demand-led services.

Taken together, these developments suggest a system stuck between increasing central control and local accountability. Local government repeatedly demonstrates that fiscal autonomy drives stronger outcomes, more responsive services and greater value for taxpayers. But selective pilots, centrally collected surcharges and delayed implementation plans do not constitute meaningful devolution.

For fiscal devolution to be effective, councils need a clear, credible roadmap: one that strengthens the link between local taxation, local decision-making, and accountability; aligns funding with demand pressures and provides long-term clarity to underpin planning and investment. Without this, councils will continue to navigate rising service pressures with uncertain powers and constrained revenue, risking both financial sustainability and the delivery of essential services.

Until that roadmap is set out, councils remain caught between rising responsibilities and delayed clarity, planning for the future without the certainty they so urgently need in the present.

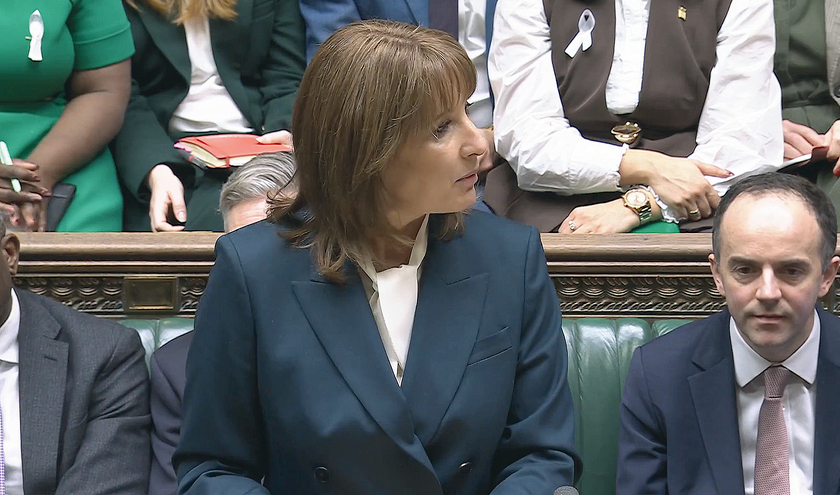

Iain Murray, CIPFA director of public financial management